Case Background

Kapila Nishshanka Kumarage v. Officer-in-Charge, Special Crimes Investigation Bureau, Police Station, Ratnapura (SC Appeal No. 51/18)

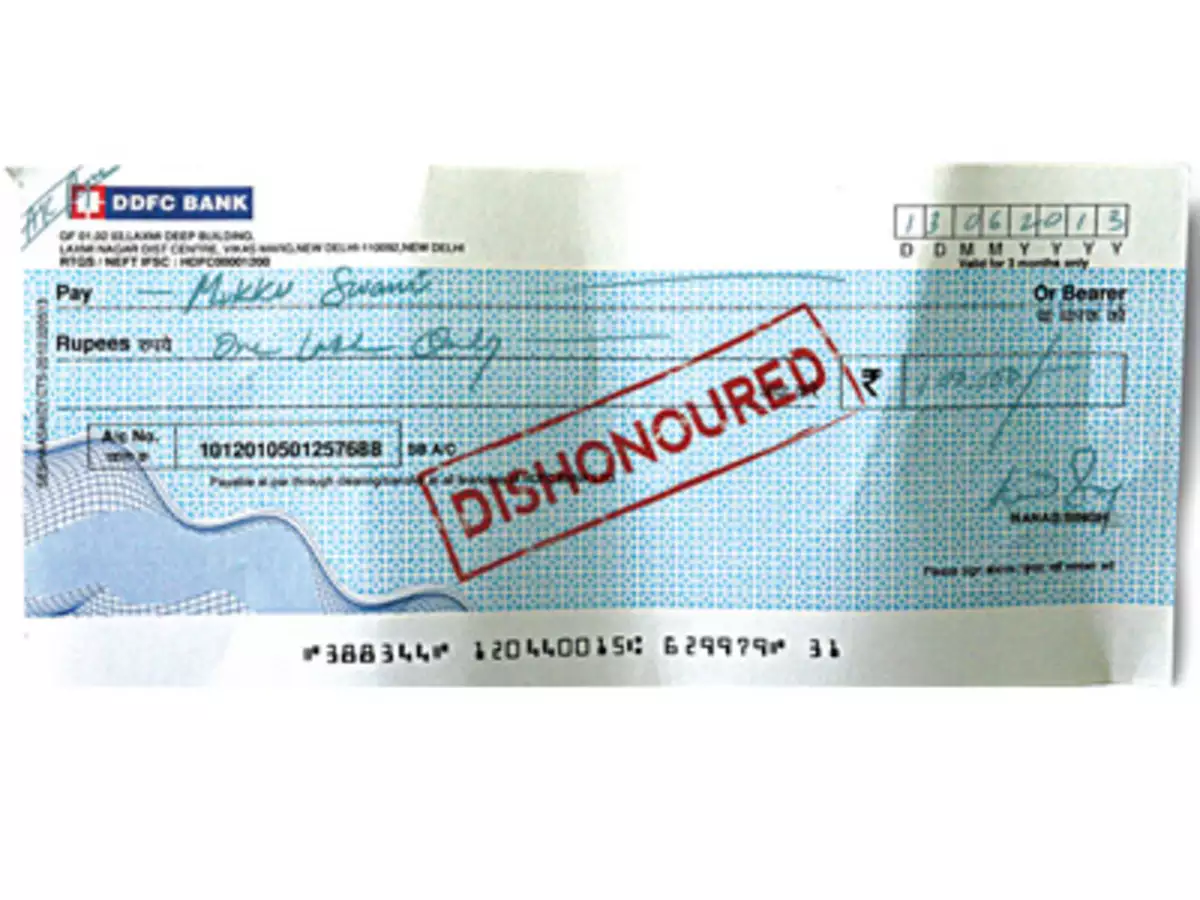

The case involved an appeal by Kapila Nishshanka Kumarage, who was convicted of the charge of “cheating” under Section 403 of the Penal Code of Sri Lanka. Kumarage had allegedly obtained a sum of Rs. 800,000 from the complainant, Kalawitigoda Pathirannalage Chandralatha, under the pretense of needing it for a business purpose. He assured repayment by providing a post-dated cheque as security, knowing that his bank account was closed. However, when the cheque was deposited, it was dishonored. Following the Magistrate Court’s conviction, which was partly upheld by the High Court, Kumarage appealed to the Supreme Court on grounds that the elements necessary to establish “cheating” were not proven.

Legal Issues

The Supreme Court focused on two critical issues:

- Mens Rea (Dishonest Intention): Did the appellant possess a dishonest intention at the time of borrowing the money, essential to establish the offense of cheating?

- Deception Leading to Financial Loss: Did the complainant provide the money due to being deceived by the accused’s actions, specifically the act of issuing a post-dated cheque from a closed account?

Court’s Findings

- Mens Rea and Absence of Dishonest Intent:

- The court emphasized that a dishonest intention must exist at the time of the loan request. While the appellant failed to repay, the court found no evidence that he initially intended to deceive the complainant. The appellant’s subsequent inability to pay back the loan did not imply a pre-existing dishonest intention, especially since the loan was requested based on pre-established trust and no explicit deceit.

- Role of the Post-Dated Cheque:

- The court noted that the cheque was given as “security” and was not the primary inducement for the complainant to provide the loan. The complainant admitted in court that her decision was based on personal trust in the appellant rather than reliance on the cheque. Since she accepted the cheque with the understanding that it was not immediately encashable, the court found that the complainant was not deceived by it.

- Closed Account and Misrepresentation:

- Although the appellant knowingly issued a cheque from a closed account, the court determined this alone was insufficient to prove “cheating.” For a conviction under Section 403, it must be shown that the issuance of the cheque directly led to the loss. The court ruled that the loan was granted on trust rather than the expectation of repayment through the cheque, negating the causative deception required for “cheating.”

- Inapplicability of Foreign Legal Precedents:

- The Senior State Counsel cited foreign cases to establish intent and deception. However, the court ruled these precedents as irrelevant to Sri Lankan jurisprudence, particularly where they address initial suspicion rather than definitive proof of intent.

- Conviction Reversal:

- Concluding that both the Magistrate’s Court and the High Court failed to assess the requisite mens rea, the Supreme Court set aside the conviction and acquitted the appellant.

Judgment and Outcome

The Supreme Court allowed the appeal, stating that the evidence did not sufficiently prove “cheating” as defined under the Penal Code. It found that the appellant’s actions were more indicative of a loan default rather than a criminal offense. The court emphasized the distinction between contractual breaches and criminal fraud, asserting that failure to repay a loan does not inherently establish intent to deceive.

Implications of the Judgment

- Strengthening the Threshold for Cheating Convictions:

- This case sets a high bar for proving criminal intent in “cheating” cases, ensuring that not all loan defaults are treated as criminal offenses. This reinforces the boundary between civil and criminal matters.

- Protecting Borrowers’ Rights:

- The judgment protects individuals who may fail to meet financial obligations without malicious intent, underscoring that mere inability to repay does not amount to cheating.

- Judicial Prudence in Foreign Precedents:

- The case serves as a cautionary example against relying on foreign jurisprudence without regard to contextual and legislative differences, promoting a Sri Lankan-specific approach to justice.

- Clarifying Evidentiary Standards:

- By requiring that deception must directly induce the financial loss, this case clarifies the evidentiary standards necessary for proving “cheating,” guiding future prosecutions in similar cases.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s decision provides a nuanced approach to distinguishing criminal intent from civil liability. It underscores the necessity for a clearly demonstrable intent to deceive and the direct causative link between deception and loss. This ruling will likely influence future legal interpretations of cheating, reinforcing a more stringent standard for establishing criminal fraud over contractual disputes in Sri Lanka.

Read Full Judgement